Truman Capote on the Dean Martin Show

“The Moth in the Flame”: An Unpublished Short Story by Truman Capote

Trump’s Plan to Scare Americans Into Supporting Car Pollution

Transportation is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in America, and the majority of it comes from cars and small trucks. That’s a major reason why President Barack Obama, in 2012, introduced a rule requiring automobile manufacturers to make their vehicles more fuel efficient—from 37 miles per gallon to more than 51 miles by the year 2025. As a side benefit, drivers would save money on gas and America’s oil reserves would last longer, reducing the incentive for energy companies to extract more of it.

But now President Donald Trump wants to “Make Cars Great Again”—by letting them remain as dirty as they are now. In an op-ed with that title in Thursday’s Wall Street Journal, the Environmental Protection Agency’s new chief, Andrew Wheeler, and Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao announced a proposal to end those Obama-era requirements. Freezing fuel-efficiency standards, Chao and Wheeler wrote, will benefit consumers by giving them “greater access to safer, more affordable vehicles.”

This claim is based on specious evidence, experts say. In truth, the administration has concocted a tortured, flimsy argument—that cleaner cars will cost thousands more, and kill thousands more people—to scare Americans into believing that the government should scrap its most consequential policy for reducing emissions.

The administration’s 978-page proposal is called the SAFE Vehicles Rule—SAFE being an acronym for “Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient”—and it argues that cleaner vehicles are more dangerous than dirtier ones. “Today’s proposed rule is anticipated to prevent more than 12,700 on-road fatalities and significantly more injuries as compared to the standards set forth in the 2012 rule,” it states. It’s not entirely clear where that statistic comes from, but as Brad Plumer explained in The New York Times, it’s based on three arguments:

First, people who buy fuel-efficient vehicles will end up driving more, increasing the odds that they will get into a crash. Second, the fuel-efficient vehicles will themselves be more expensive, slowing the rate at which people buy newer vehicles with advanced safety features. Third, automakers will have to make their cars lighter in response to rising standards, slightly hurting safety.

Dirty cars, in other words, are heavier—and when heavy cars get into accidents, the people inside them are less likely to die. Thus, the administration argues, “It is now recognized that as the stringency of [fuel efficiency] standards increases, so does the likelihood that higher stringency will increase on-road fatalities. As it turns out, there is no such thing as a free lunch.”

But this argument has been “largely debunked,” David Greene, a civil and environmental engineering professor professor at the University of Tennessee professor, told E&E News. “The problem with that argument is that it didn’t take into account that all of the light-duty vehicles would be made lighter,” he said. “That leads to a simple physics equation—if all cars are lighter, there’s less kinetic energy involved in any crash. Therefore, the force between two vehicles is reduced when they collide.”

It’s also unclear whether increased fuel efficiency causes people to drive more, by any substantial amount. As Plumer noted, the Obama administration’s estimate was that people would drive about 0.1 percent more for every 1 percent increase in fuel efficiency. The Trump administration’s analysis found that the “rebound effect,” as it’s called, would be about twice as high as Obama’s analysis said—though that’s still not a very significant increase.

Experts also questioned the argument that lighter cars will cause more deaths. “The most important question is whether cars on the road are getting more similar in weight, or more dissimilar,” Mark Jacobsen, an economist at the University of California, San Diego, told Plumer. “If you’re bringing down the weight of the heaviest vehicles but not the lightest vehicles, then in the average accident, the cars will be better matched.”

The Trump administration admits that, under its proposal, both fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions would increase by about 4 percent. But it argues that if automakers are forced to make cleaner cars, which may cost slightly more, people will hold onto their dirtier cars for longer. Thus, “smog-forming pollution would actually decrease” by 0.1 percent.

Dave Cooke, a senior vehicles analyst at the Union of Concerned Scientists, doesn’t buy it. “There is no consistency to this logic,” he wrote. “They claim that these newer and more efficient vehicles will be so great that everyone will travel more, but not so great that people will want to buy them.” He argued that car manufacturers have been doing well since fuel efficiency standards have been in place. Currently, they’re “on pace for 17 million in annual sales for the fourth consecutive year, extending an industry record.”

The administration can’t say it wasn’t warned about the flaws in its logic. According to The Washington Post, an earlier version of this proposal was presented to the EPA’s Office of Transportation and Air Quality, and officials said it contained “a wide range of errors, use of outdated data, and unsupported assumptions.”

As the Trump administration claims that freezing fuel efficiency standards will actually reduce pollution, it also ignores the health benefits of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The draft proposal explicitly notes that it would only consider the domestic—not global—health benefits of slowing climate change. That could reduce the estimated climate benefits from the Obama-era car rules by about 87 percent, according to a recent paper.

On Thursday morning, 20 attorneys general pledged to sue the Trump administration over the proposed rule. That afternoon, White House press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders tried to soften the administration’s position, saying that the proposal “asked for comments on the range of options. We’re simply opening it up for a comment period, and we’ll make a final decision at the end of that.”

But Trump’s aims here are clear, and so are the consequences. Weakening the Obama standards “would clear the way for vehicles to, by 2030, spew an addition 600 million metric tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere—equivalent to the entire annual emissions of Canada,” HuffPost reported. That’s also equivalent to “firing up 30 coal power plants,” said Paul Cort, a lawyer with Earthjustice. And to justify this regressive policy, Trump is using two familiar ingredients: fear and falsehoods.

Among the Extremists on Campus

Campus novels have always been about much more than university life. When in 1954 Kingsley Amis published Lucky Jim—perhaps the most widely read contribution to the genre—conventional wisdom held that the campus was a place of intellectual pretensions and retrograde hierarchies. Amis narrated and satirized the tribulations of a haphazard lecturer, but his true target was the vicious class hierarchies that lingered in postwar Britain despite the nation’s promise to democratize. The university was not a closed system but a sandbox in which students and faculty played out social troubles that were roiling the country.

R.O. Kwon’s debut, The Incendiaries, squats subversively in this tradition. The novel begins with a disaster near Edwards University, its fictional East Coast school: “The Phipps building fell,” recounts Will Kendall, its student narrator. “Smoke plumed, the breath of God. Silence followed, then the group’s shouts of triumph.” The group is a cult of Christian fanatics, and they have bombed an abortion clinic. Among them is Will’s college love, Phoebe Haejin Lin, who has left him after a relationship defined by his obsession and violence. Against the notion that college today is a hotbed of left-wing radicalism disconnected from the real world, Kwon tells a story of right-wing extremism embedded in a patriarchal order.

How has Phoebe become a zealot? “You once told me I hadn’t even tried to understand,” Will imagines saying to her. “So, here I am, trying.” Bound by his own worldview, he never quite manages. Kwon’s lush imaginative project is to help us understand for him. With the needle of her prose, she plucks at the fabric of the university, exposing the reactionary impulses that run through American life.

A “juvenile born-again” who has lost his faith, Will arrives at Edwards by way of bible college with his soul a gaping void. There he gravitates toward the old-boys network. He pledges Phi Epsilon and works internships at financial institutions, lying about his modest background and his side job waiting tables (“I wanted a new life, so I invented it”). But all this comes second to his dramas with Phoebe, a Korean-American student he meets in his first term, and John Leal, the leader of the cult. They fill the “God-shaped hole” in him.

The abiding sense of purpose Will finds in Phoebe quickly tips into infatuation and controlling behavior when she proves elusive. Not knowing what he has “the right to ask” her, Will indulges lurid fantasies in passages like “I imagined Phoebe’s sidling hips, the fist-sized breasts” and “I bit her lips. I licked fingers; I grabbed fistfuls of made-up skin until, sometimes, when I saw the girl in the flesh, she looked as implausible as all the Phoebes I’d dreamed into being.” These dorm-room images—the aggressive porno-poetry of fists and biting and grabbing—establish the push and pull of their relationship. Having “claimed each inch of Phoebe’s skin” is not enough. He rifles through the notes in her books, seeking to channel the “shining, inmost psyche” she withholds from him. His desire is wholesale possession.

Kwon weaves this power dynamic into the fabric of the novel itself, allowing Will to speak in Phoebe’s voice. What often sounds like her first-person account is in fact Will ventriloquizing. Through him, we learn she was a sheltered child pianist who quit when she discovered her limits (“I hoped I’d be a piano genius”). She’s wracked with guilt and grief at her mother’s recent death, which resulted when she crashed their car during an argument. She’s “broken, desperate for healing.” But trust Will like you trust Charles Kinbote, the self-deceiving narrator of Vladimir Nabokov’s kaleidoscopic campus novel Pale Fire—which is to say don’t trust him at all. In truth, we have no idea what of Phoebe is “real” and what’s a figment that he has “dreamed into being.”

Will and Phoebe haven’t been together long when the mysterious John Leal, a former Edwards student, strides barefoot into the narrative. An incursion from the outside world, he serves as Will’s double and rival. Where Will wants Phoebe’s mind and body, John wants her soul. Where Will has lost a God, John has lately gained one—an outcome, he claims, of time he spent imprisoned in a North Korean gulag for his role in shuttling refugees from that country into China. He knows Phoebe’s father, from whom she’s estranged. He too has lost a mother. No matter that his story never quite adds up. “If you can find delight in this lack as you did with presence, you’ll gain what you think is lost,” he says, in one of his typical spiritual riddles. The promise he offers is relief from suffering. But it has its costs.

Part of The Incendiaries’s power lies in the way Kwon contrasts this campus with stereotypes of American campus culture today. When, for example, a friend of Phoebe’s accuses another student of rape, she’s met with immediate doubt and backlash, even as Phoebe defends her. It’s easy to decry student appeals for “safe spaces” on campus, but harder to remember that, for certain students, neither campus nor the world that surrounds it is reliably safe.

Fittingly, the strongest bond in the book forms between the men who represent this lack of safety. It’s unlikely that Will, who studies finance, reads gender theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s seminal work on male “homosocial” desire during his time at Edwards. But, if he did, he might notice the classic “erotic triangle” that his relationship with John and Phoebe constitutes. Whether friends or rivals, the men’s power struggle serves to uphold a toxic status quo. “In any male-dominated society,” Sedgwick argued, “there is a special relationship between male homosocial (including homosexual) desire and the structures for maintaining and transmitting patriarchal power.” This kind of stuff got Sedgwick maligned by conservative academics as a

“tenured radical.” But she wasn’t wrong.

You can see how this works in practice when Will and Phoebe visit the cult house. By the end of the night, John has thrust his hand creepily into Phoebe’s purse while she holds it open for him: “He dipped his fingers into the bag’s opal slit. The bright satin lining showed. I’d have liked to stop him, but she let it happen. The bag might as well have been his.” Will looks on in horror at this intimate usurpation. In moments like this, Kwon signals to the reader in Freudian dream-terms just what’s at stake between these men. Their tactics are different, but their claims are the same.

Gradually, the power balance shifts. Phoebe immerses herself in faith, and Will loses his grip on her. The cult Kwon has imagined is into pretty standard stuff, but their confession rituals and absolution rites escalate to flagellation and anti-abortion violence. Here’s that reactionary strain. “I’ll ask you what I’ve asked myself, late at night, as I wait upon His Spirit: if the likes of you and I won’t be radical for God, who will?” says John Leal to a crowd of demonstrators outside a clinic.

As Will retreats from the cult, he tries to understand why Phoebe tolerates this call to violence, or at least to simulate understanding for the gentle reader:

This situation, well, it was a crisis. The girl I loved was in a cult—and that’s what it is, I thought, a cult. It was a problem, but I’d solve it, because I was intelligent. The sun’s heat intensified. Disquiet thawed until, tranquil, awash, I almost sympathized with these people. If I were convinced that abortion killed, I, too, might think I had to stop the licit holocaust. It wasn’t so long ago that I’d believed as they did. In fact, I pitied them.

Pity, of course, can be its own form of cruelty. And all this comes before Will commits his final, awful act of domination. “I kept seeing the point in time, and choice, when I pressed Phoebe down against the floorboards,” he reflects. “She’d flinched with pain, then surprise. I’d found it satisfying: I enjoyed frightening the girl I loved.” Admire the matter-of-factness with which Kwon, in both of these passages, invokes the phrase “the girl I loved.”

If nothing else, it helps illuminate why it feels not just wrong but malicious when commentators dismiss college as a kind of four-year escape from reality, where left-wing professors indulge spoiled students’ frivolous identity explorations and demands for safety. The truth is that the campus is the exact opposite of an escape. It’s a place that confronts kids who are barely out of adolescence with the most distressing and complicated realities of American life: the cultural claims of love that routinely justify violence, the limits on autonomy for whole classes of people, the protections afforded to some and not others, the social systems that underwrite it all. It requires that students, in a very short time, make real and serious decisions about who they are, what they value, and how they’ll respond if they find themselves implicated. Who wouldn’t seek reassurance?

There are moments when Kwon’s novel verges on didactic. She sometimes puts lessons in her characters’ mouths that they’re ill-suited to deliver, as when Will’s boss, a tough-talking fraud, fires back at Will for questioning him: “If you’re hoping to wipe down that soul of yours, do it on your own time.” There are other odd bits of reader wish-fulfillment as Will leaves the campus and Kwon brings the novel to an uneasy close.

In the same way The Incendiaries isn’t about religion or the “culture wars” or abortion, it also doesn’t try to create a believable world of college kids or, really, a believable world at all. Instead, it’s an impression of the mysterious social forces and private agonies that might drive a person to extremes. Losing faith is painful because it sends you grasping in all sorts of directions for the “illusion of love,” as Will’s boss puts it, that everyone else is seeking. But gaining faith can be painful, too. For the disempowered, it might mean a further loss of agency. Phoebe escapes Will’s narrative, but Kwon offers no easy answers.

What lingers is a sense of understanding, a rare bit of actual wisdom from the cult. “I often thought about what John Leal liked saying,” Phoebe says, “that if we could believe all people existed in their minds as much as we did in our own, the rest followed. To love, he said, is but to imagine well.” Imagining what others experience, even if those people are loathsome and violent, is as much a literary task as a spiritual one. It’s not a solution to extremism, but it’s a beginning.

When Fascists Turn Violent

Yiannis Boutaris stared back at a sea of angry faces on May 20—a few muttered insults. Boos erupted from pockets of the crowd. “Leave,” they demanded.

The 76-year-old winemaker-turned-mayor’s body tensed: “I heard voices from here and there, and these voices came little by little closer,” Boutaris recalled.

More people joined in the jeers, and he suddenly realized he was surrounded.

Boutaris first became mayor of Thessaloniki, Greece’s second-largest city, in 2011. A reed-thin recovering alcoholic who hasn’t “even smelled whiskey for the last 27 years,” he has a timeworn face, a silver stud in his left ear, and tattoos on his arms, hands, and fingers.

His tireless advocacy for LGBTQI rights, outspoken opposition to unchecked nationalism, and push to highlight the city’s Ottoman past and Jewish history have made him a central target of Greece’s far right. In seven years as mayor, Boutaris has championed Pride parades in the northern coastal city, initiated plans for a Holocaust memorial museum, and expanded tourism from Turkey, Israel, and the Balkans.

In early 2018, right-wing nationalist sentiments building throughout Greece over the refugee crisis and economic troubles erupted in protests tied to the ongoing naming dispute between Greece and neighboring Macedonia. On January 21, hundreds of thousands poured into the streets of Thessaloniki to oppose any inclusion of the word “Macedonia,” which is also the name of a northern region of Greece, in the official title of the former Yugoslav republic. Amongst banners reading “There is only one Macedonia and it is Greek!”, some far-right participants distributed fliers dubbing Boutaris a “slave of the Jews,” and others attacked a pair of anarchist squats, setting one ablaze. By the time the squares and streets emptied, unknown assailants had defaced the Holocaust monument in the city center. They left behind the logo of the neo-fascist Golden Dawn party, which first entered parliament in 2013.

Although he had long been an obsession of the far right, Boutaris began to receive threats and hate mail more frequently. He ignored most of them. “Since I took over [as mayor], I have calls, I have letters saying, ‘you are fucking Jew,’ ‘you are a fucking Turk,’” he said.

But at the annual commemoration event in May, a mob attacked him.

Boutaris has attended every commemoration of the early twentieth-century Turkish killings of ethnic Greeks since assuming office. Although only two weeks past a heart operation this May, he was determined to attend the ceremonies held throughout the city. In an unassuming navy suit—tieless, but with a commemorative yellow badge on his lapel—Boutaris went from one event to the next. Last on the day’s program was a flag-lowering ceremony at Thessaloniki’s White Tower monument, situated on the three-mile promenade tracing the city’s coastline.

Leaving the small black sedan on a nearby street, Boutaris, his driver, a bodyguard, and Kalypso Goula, the president of Thessaloniki’s city council, approached the tower where more than a thousand people were already present.

Panayiotis Psomiadis, the right-wing former regional governor of Thessaloniki, cursed at the approaching mayor. Boutaris stopped near the tower.

Boutaris wasn’t fearful when the shouts first started, but the hostility swelled. The moment lingered, pregnant with tension until someone in the back shouted, “Let’s go.”

Within seconds, he was encircled by frantic young men, who shoved him and spat. Bottles flew in his direction. A punch came, and then another. His small entourage gripped him by his rawboned arms and guided him toward the car as the mob lashed out at them, several punches landing on city council president Goula as well. The attackers followed, some sprinting from the back to catch up. A tall, limber young man in a black, skin-tight Everlast shirt and matching athletic shorts delivered a series of powerful kicks to the mayor’s sternum. Boutaris lost his balance and tumbled to the ground, the crowd kicking at him. The guards got him back up. Finally, they reached the car, Goula prying open the passenger-side door. Boutaris slid in, and the car sped away as a final string of strikes burst the rear window into a scatter of jagged shards.

Goula stayed behind: The mob’s anger was gone, and in its place was deafening applause.

In Greece,

far-right violence isn’t new. Vigilante attacks and far-right gangs were common

during the meteoric rise of Golden Dawn during the 2012 parliamentary elections. Modeled off German national

socialism, the party’s street-roaming

assault battalions paved the way for other would-be attackers seeking to

redirect blame for the country’s economic crisis to foreigners, leftists, and other

political opponents. A brutal wave of violence, mostly targeting migrants, reached

a climax in September 2013, when a Golden Dawn member stabbed to death 34-year-old anti-fascist rapper

Pavlos Fyssas. Following that murder, much of the party’s leadership was

arrested, and 69 members are still on trial for allegedly

operating a criminal organization. The rising tide seemed, finally, to have

ebbed.

In the last year, though, a startling resurgence of xenophobic violence has again worried observers. From 2016 to 2017, the number of hate crimes documented by Hellenic Police more than doubled, growing from 84 to 184 incidents. In early 2018, the violence showed little signs of letting up. Fueled by frustration over the refugee crisis, anger over the Macedonia name talks, simmering tensions with Turkey, and discontent with the left-wing-led government, protests were staged in several cities, and xenophobic violence regularly made headlines: Pakistani migrant workers were attacked in their homes and in fields, refugees were pelted with bottles and stones on Greek islands, and non-profit organizations working with refugees received a spate of death threats. Jewish memorials and cemeteries were desecrated several times in Thessaloniki and Athens, and a neo-Nazi group, Crypteia, took credit for an arson attack on the Afghan Community of Greece’s office in March.

Foreign Minister Nikos Kotzias has received more than 800 death threats against himself and his family this year, he told the Greek radio station 247 FM in June. Prompted by the name talks with Macedonia, they included envelopes containing bullets and boxes of blood-soaked soil.

“I don’t know that it’s a revival, I think it’s always been there,” University of Reading professor and Golden Dawn expert Daphne Halikiopoulou said of recent developments, explaining that there is a long history of far-right political violence in ebbs and flows. “Drawing on this nationalism at a time when Greek people are quite radicalized because of the crisis and discontent, makes [violence] okay [for some].”

Boutaris was lucky: His injuries turned out to be minor. But after the attack, police officers insisted that the mayor go to the hospital. Inside, he spotted one of his attackers being bandaged in the corner.

The attack rattled Greece and captured national and international headlines, signaling the far right’s willingness to carry out violence in broad daylight. Several people were arrested over their alleged involvement, including a 44-year-old police officer and a minor. Political parties across the spectrum issued formal condemnations, and the Pontic organizations that hosted the event denounced the violence. Syriza described the incident as a “fascist assault,” while the center-left Movement for Change political alliance called it “embarrassing” and “unacceptable.” Although the right-wing opposition party New Democracy decried the attack, left-wing Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras accused the party of contributing to nationalist sentiments, saying it “lays out a carpet for the far right.”

Some, though, reveled in the moment. In the northern city of Kavala, Christos Paschalidis, an ultra-nationalist official, wrote on Facebook that Boutaris “got what he deserved.” Writing on Twitter, Dimitris Kambosou, the mayor of the southern village of Argos, rushed to label Boutaris a “traitor” for his moderate position on the Macedonia re-naming in the wake of the incident. (Weeks later, New Democracy expelled Kambosou over an intensely anti-Semitic rant in which he said Boutaris “can say what he wants because he wears the [kippah].”)

Golden Dawn openly praised the incident. A party statement celebrated it as “popular rage,” and a separate press release accused Boutaris of “tarnishing” the commemoration’s sanctity. Ourania Michaloliakou, the daughter of Golden Dawn chief Nikolas Michaloliakos, complimented the assailants. “Bravo to each and every one who carried out his duty in Thessaloniki today,” she posted on Twitter. “Respect.”

The response, Halikiopoulou said, “actually highlights the absence of liberal thought in Greece. It shows that many semi-accept that it is okay to punch people in the face for having different ideas.”

Threats, intimidation, and physical violence have failed to deter Boutaris so far. Reelected in 2014 by those who favor his liberal policies, he plans to run for a third term in May 2019. Though under no illusions about the fragile political climate, he insists he will continue his efforts to foster a more tolerant climate in the city and broaden tourism from diverse countries: Racism and xenophobia, he believes, have no future in Greece.

“I am considered a traitor because ‘I love Turks,’ ‘I love Jews,’ I love gays,’ ‘I love refugees’… This is totally foolish, so I don’t pay much attention anyway,” he said. Taking drags from a filter-free cigarette, he sat on a July afternoon in a deep, cushioned chair in his souvenir-adorned office. A dull black-and-grey lizard hand tattoo wriggled as he crushed the cigarette into an ashtray. On his desk lay a cluster of folders and papers. “If I am a traitor, I ask them: What did you do for your country apart from saying ‘Alexander the Great’? Alexander the Great died more than two thousand years ago. Did you create jobs? Did you support the market [through] tourism?”

Since he was attacked, people passing Boutaris’s home have yelled and cursed at him. He remembers the attack clearly: coaching himself to remain calm. He also remembers the small child one of the men cradled while chasing him, shouting.

“Nationalists are always violent,” he said. “They don’t hear anything else other than what they believe.”

Apple’s Stock Market Scam

Apple beat Amazon and Google in the race to become the first trillion-dollar company in the U.S. on Thursday afternoon, when its stock hit $207.0425 a share. (It closed slightly higher.) It’s another milestone for what might be the most important company of the century thus far—one that’s even more impressive given that, 20 years ago, the company was being written off by nearly everyone and was on the verge of bankruptcy. But Apple survived both near-bankruptcy and the 2011 death of the company’s visionary founder, Steve Jobs. BusinessWeek marked the achievement with a bit of self-deprecation, tweeting its 1997 cover on “The Fall of An American Icon.”

LOL pic.twitter.com/Z0Z0c2CaEs

— Businessweek (@BW) August 2, 2018

The road to a trillion was paved with iPods, iPads, and iPhones—and, crucially, with the rollout of stores that NYU Stern School of Business professor Scott Galloway has described as “temples to the brand.” But Apple’s recent success on Wall Street isn’t due to its technological innovations or its sleek products. Instead, its stock has been juiced by a record-breaking number of buybacks, in which the company buys shares of its own stock, causing the supply to drop and the price to rise. In May, several months after Congress passed a massive corporate tax cut, Apple pledged $100 billion to stock buybacks in 2018—and is halfway to that goal. With $285 billion in cash on hand, it can afford to buy even more.

Viewed over a period of decades, a number of products and achievements played a role in getting Apple to where it is today. But as the company’s profit margins have shrunk, stock buybacks played a crucial role in getting Apple over the trillion-dollar finish line first. This asterisk should be something of a scandal. Apple is the poster child of the current spate of stock buybacks, which are starving investment and exacerbating inequality.

Though never banned outright, buybacks were largely curtailed in the wake of the Great Depression, thanks to rules that limited the ability of corporations to manipulate their own stock. As Vox explained earlier this week, even the threat of action largely kept buybacks from happening: “Companies knew that if they did a stock buyback, it could open them up to being accused by the Securities and Exchange Commission of having tried to manipulate their stock price, so most just didn’t.”

But as enforcement loosened, notably under the Reagan administration, buybacks began to increase. Now, they are omnipresent. A Roosevelt Institute study released on Tuesday found that corporations spent 60 percent of their net profits on stock buybacks between 2015-2017. Buybacks have continued to boom in the wake of the $1.5 trillion tax cut passed in December. J.P. Morgan estimates that $800 billion will be spent on buybacks in 2018, obliterating the previous record of $587 billion in 2007—a spree that ended when the economy collapsed.

The goal of buybacks is straightforward: They prop up share prices and reward shareholders by increasing the value of the piece of the company that they own. There is no conclusive evidence that buybacks boost share prices in the long term, but as The Motley Fool explains, “In the near term, the stock price may rise because shareholders know that a buyback will immediately boost earnings per share.” But buybacks may not be a particularly efficient way to prop up a share price. Earlier this month, The Wall Street Journal found that “57% of the more than 350 companies in the S&P 500 that bought back shares so far this year are trailing the index’s 3.2% increase.” (Apple’s stock, however was an exception—its shares had jumped 11 percent at the time of the report.) Nevertheless, given the amount of pressure that CEOs are under, and the fact that buybacks are applauded by the shareholders that profit from them, it’s no wonder that public companies in the U.S. have spent the majority of the windfall they received from last year’s tax cut buying back their own stock.

Because companies are spending so much on buybacks, they’re neglecting to invest in their workers or their products. “Stock buybacks undermine the productive capabilities of companies and their ability to generate new products that compete on the market, and this is going to, at some point, show up in stock price,” University of Massachusetts professor William Lazonick, who studies buybacks, told me. Buybacks, as the Roosevelt Institute study found, also keep wages low by giving money to shareholders rather than investing it in workers.

All of this is direct result of the short-term focus of the economy. “I attribute it a lot of it to the financialization of the economy,” Lazonick said. “Once you’re willing to spend two or three or four billion or more a year on buybacks for a large company, you start becoming much more willing to lay off 5,000 people even in a prosperous period to pump your stock price up.”

Tim Cook, Apple’s CEO, has argued that stock buybacks are ultimately good for the economy, because investors have to pay capital gains tax when they sell stock. This is something of a novel argument—it was made in a MarketWatch article published a few days earlier—but it’s not a particularly convincing one because most of the money would go directly to shareholders and executives, rather than the government or workers. Cook’s argument is also at odds with history. “Usually the conventional wisdom is the opposite,” John Cochrane, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institute, told Business Insider. “Stock buybacks started in the 1990s as a way of helping people to avoid taxes.”

Apple has pledged to add 20,000 jobs this year, but little is known about what exactly that means. Apple has increased its research and development spending over the past year, but the company is still only spending about five percent of total sales, a relatively low number, especially given the fierce competition between Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft. And consternation among investors about how that money is being spent—Apple’s biggest product of the last few years is the AirPod wireless headphones, which aren’t exactly the iPod, whatever Cook says—may be playing a role in Cook’s decision to buy back so much stock.

Apple is, by its own standards, in a bit of a lull in terms of profit margins. But the company has so much money on hand that it can afford to spend billions to keep investors happy, buying itself some time to develop the next breakthrough product. Ultimately, Apple crested the trillion-dollar mark not through technological brilliance, but stock manipulation. That’s hardly cause for popping the champagne.

A New David Wojnarowicz Exhibition on His Old Cruising Grounds

In the new David Wojnarowicz show at the Whitney, there’s a room with nothing in it. A 1992 recording of the artist reading from his memoir Close to the Knives plays to the white walls. The blinds are drawn on the room’s single window. If they weren’t, you’d be able to look out over the Hudson River Park, where derelict shipping piers once stood. Wojnarowicz cruised those piers, wrote about them, painted on their ruins. There’s no sign of them now.

Wojnarowicz’s New York is gone, and so is he; he died of AIDS in 1992, at age 37. The nature of his death is the thing people are most likely to know about him, apart from the facts that he had a beautiful face and a terrible childhood, and hustled as a teenager in Times Square. The most famous images he made are about homophobia and AIDS. The poster for the 1989 Rosa von Praunheim film Silence = Death, which shows him with his lips sewn shut, comes directly from his 1986-7 art film Fire In My Belly. The 1990 work Untitled (One Day This Kid…) frames a picture of Wojnarowicz as a child with a series of declarations: “One day politicians will enact legislation against this kid....Doctors will pronounce this kid curable as if his brain were a virus....All this will begin to happen in one or two years when he discovers he desires to place his naked body on the naked body of another boy.” These works function as advocacy as much as art.

Because the best-known pieces in Wojnarowicz’s oeuvre draw from his direct experience, the curators of the museum’s retrospective, David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake At Night, were stuck in a bind: To what extent would the show commemorate the man, and to what extent would it focus on the art? They seem to have gone with “as much as possible of both.” The nine rooms hold paintings, prints, collages, photographs, and journals, as well as films and recorded music, drawn from the last decade and a half before his death—the only thing the exhibition stops short of including, it seems, are the walls of the East Village building on which Wojnarowicz stenciled the image of a burning house.

This maximalist approach is thrilling but can feel somewhat incoherent, an effect not least of the sheer breadth of media Wojnarowicz employed. Among his most affecting projects is a series of black-and-white portraits he took of himself and his friends, each in delicate chiaroscuro. In his 1980 study of Iolo Carew, fingers flutter over skin. The pictures are poetic, the kind of thing that you want to see in isolation so that you can swoon over them in peace. The most famous are a trio he took of Peter Hujar, his long-time friend and sometime lover, just after Hujar’s death. One shows the man’s Christlike, absent face. The next, his hand. The next, his feet, toes bunched together. What I felt looking at these photographs must be what devout Catholics feel when they look at images of suffering saints.

In another black-and-white series, which he called Arthur Rimbaud in New York, Wojnarowicz dressed friends in a mask of the French poet’s face and photographed them in places that had been important in his own life (Times Square, Coney Island, the piers). The prints are quite small and modest. In an adjoining room, meanwhile, hang his stencil works—big, bright collages mixing Kraft posters and maps and images of sex. Playing in the background is a recording of Wojnarowicz’s tinny band 3 Teens Kill 4. The contrast between the rich Rimbaud material and the jittery mood of the stencil room is jolting.

Hujar proves to be the link between the soulful photographs and the more antic colorful work. A series of works with the words “Peter Hujar dreaming” in their titles juxtapose outlines of that man in repose with bright acrylic-painted backgrounds and the stenciled shapes that Wojnarowicz grew so fond of. Peter Hujar Dreaming /Yukio Mishima: Saint Sebastian (1982) is the best of them. You can see the photographs’ elegance in the grace of the reclining form, but the color-blocking behind it adds a special force.

Perhaps the finest images, however, are Wojnarowicz’s rhetorically powerful screenprints, in which he joins text and image to speak truths about AIDS, as in the 1990s work Untitled (ACT UP). The work consists of two prints. The first layers a breathless rush of words in green lettering over black-and-white images of floating bodies: “I was told I have ARC recently and this was after watching seven friends die in the last two years slow vicious unnecessary deaths because fags and dykes and drug addicts are expendable in this country ‘If you want to stop AIDS shoot the queers’ says the ex-governor of texas,” it reads. (ARC was a common way of referring to HIV-positive status at the time.) The other layers a stock-market printout, in green, over a bull’s-eye in the shape of the United States. Like Untitled (One Day This Kid...), the prints advocate for the destigmatization of HIV/AIDS. They are elegant images that are optimized for mass communication. They are designed to be seen out in the world, not hidden in a gallery.

This summer, Semiotext(e) published transcripts of Wojnarowicz’s audiotape journals, mostly recorded between 1987 and 1989, which until now have languished in NYU’s Fales collection. Wojnarowicz was a fine writer, as can be seen in his memoirs Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration (1991) and Memories That Smell Like Gasoline (1992), and in his many catalogue essays and diaries. Close to the Knives opens with Wojnarowicz’s recollections of street life in Times Square, memories of hallucinating from hunger and marketing his body to pedophiles. Elsewhere, he writes of those piers on the west side, “night in a room full of strangers, the maze of hallways wandered as in films.” This new volume, titled Weight of the Earth, shows a different side of him. It is a record of the present rather than a recreation of the past—he is preoccupied with dreams, little romantic dramas, what he feels like eating for dinner, his health.

Wojnarowicz used the audio diary to record his thoughts as they happened, and the transcripts have an off-the-cuff immediacy that is hard to find in the Whitney show. He describes a shift he worked at the Peppermint Lounge, muses on a fling he’s in the middle of—“I think of the silliest things,” he interrupts himself to say. He knows he has “ARC,” the term in currency then to describe being HIV positive, but he isn’t interested in memorializing himself in some grand way. He made masks of Rimbaud, he didn’t want to be Rimbaud. “I don’t think about death very much,” he says, “because it won’t let itself be thought of.”

Yet the presence of death inevitably made his days more vivid. In one journal entry, made while on a road trip, Wojnarowicz describes “a mortality hallucination,” a moment in which he realizes “just how alive I am and also the impermanence of it”:

Yeah, I’m alive, but, you know, I could be dead another year from now or two years from now. And I won’t see this road, and I won’t see the sunlight, and I won’t see these fast trucks driving by—the long, long road up ahead of me, and a long, long road in the rearview mirror. And time just moves so slow, and time moves so fast—and then time stands still for some, and time just speeds up for others. For me, at this moment, I’m in quite a dislocation of time, from both outside of time and inside of time at the same time. And all the world looks pretty great.

The joy Wojnarowicz took in his work—the joy of bright color and the sheer beauty of being a living body—resists museumification. All those strange paintings, the tender photographs, the audio diaries, even the silly band—everything exists passionately in the present tense. He cared about how the light reflected off the trucks, not about understanding death. And so this museum’s attempt to make for him a legacy, to delve inside the man as political symbol and to unite that identity with his playful art, just doesn’t quite work. If death won’t let itself be thought of, it certainly won’t let itself be curated.

New York will never be a neutral place in which to look back on the history of New York, or at the people who have lived and worked here. It’s a place with a truly abnormal way of treating memory. As communities engaged in frantic remembrance of all the people who died of AIDS—whole groups of friends just deleted by its breathtakingly rapid spread—their mourning got digested by institutions into themes, grad school classes, and nostalgia, even as people throughout the city are still living with the illness. Wojnarowicz’s activism defined how we see his work. How could it have been otherwise? He lived and worked during an epidemic that eventually took his body, too. We still need symbols of resistance against misinformation and stigma, because we are still defending the rights of queer people to medical access, to lives lived free of abuse, to visibility amid normative culture. But a symbol is not the same thing as an artist. The works on display at the Whitney show that although Wojnarowicz has become a very specific icon, his art had many strands. Wojnarowicz sewed his lips shut to protest the silence that helps HIV/AIDS flourish, not because he wanted to make himself mute. Wojnarowicz the symbol sits uneasily beside the flowering multiplicity of his work. This show is a rare chance to see the many David Wojnarowiczes at once, beside one another; just don’t mistake the poster for the man.

Don’t Call a Harassed Writer a Neo-Nazi

Tech journalist Sarah Jeong, recently hired to the editorial board of The New York Times, became the target of venom and outrage Wednesday and Thursday after conservative outlets found and published collections of her old tweets, which contained complaints about white people. “Are white people genetically predisposed to burn faster in the sun, thus logically being only fit to live underground like groveling goblins?” read one tweet, published in a National Review article.

As of Thursday, Fox News, The New York Post, and The Daily Caller had all run stories that referred to Jeong’s tweets as “racist” either in headlines or in the body of an article. On Twitter, a number of right-wing writers took up the claim. Andrew Sullivan, writer at large for New York Magazine, shared a retweet of the post that started the furor, published at far-right pro-Trump website Gateway Pundit. At the American Conservative, Rod Dreher called Jeong a “honky-hater.” The Week’s Damon Linker called Jeong “a racist. A flagrant one--one whose views are indistinguishable at the level of principle from Richard Spencer’s. She just hates different groups.” Incredibly, Linker was not the only writer to invoke Spencer—a prominent white supremacist whose Third Reich salutes and imitations of Nuremberg rallies have made it clear he is in fact a neo-Nazi. “Richard Spencer is more subtle than this woman,” tweeted Geoffrey Ingersoll of The Daily Caller.

On Wednesday afternoon, the Times published a tepid defense of Jeong, saying she would keep her job. Jeong’s work, race and gender “made her a subject of frequent online harassment,” the Times wrote. “For a period of time she responded to that harassment by imitating the rhetoric of her harassers. She sees now that this approach only served to further the vitriol that we too often see on social media. She regrets it, and the Times does not condone it.”

For those intimately familiar with the sort of harassment women, non-binary people, and people of color face online, these episodes can be maddening to watch play out. Though defending Jeong, the Times did not explain why Jeong’s tweets were different, for example, from those of Quinn Norton, who lost her own new gig at Times in February over her friendship with a white supremacist, in addition to tweets containing racist and homophobic slurs. And as these controversies proliferate—another took place at The Atlantic in April, involving conservative writer Kevin D. Williamson—failing to advance a clear vision of what is and is not acceptable in public discourse only plays into conservative narratives about leftist hypocrisy, leaving many minorities as vulnerable as ever.

To cite one example: At New York Magazine, Sullivan argued on Friday that “today’s political left” believes Jeong “definitionally cannot be racist, because she’s both a woman and a racial minority.” Instead, he declared, leftists believe “racism has nothing to do with a person’s willingness to pre-judge people by the color of their skin.” But Sullivan’s straw man misses the entire point of the leftist argument: Racism is about prejudice, but it is also about power imbalance (a definition Sullivan himself rejects). Jeong might have imitated the tone of her harassers, but she did not imitate the substance of their vitriol, and that distinction is key. Jeong’s harassers subjected her to racist, misogynist hate speech; they punched down. Not only did Jeong punch up, she did so as a reaction to sustained abuse.

No reasonable person would entertain a comparison between a woman of color, who occasionally loses her temper at her trollers, and a neo-Nazi. That’s not because women of color are inherently sacred, as Andrew Sullivan’s caricature of leftist thought posits, but because they belong to a class subject to centuries of institutional violence and social marginalization. Jeong’s tweets are distinct from those of Quinn Norton, who lost her own new gig at the Times for tweeting homophobia and befriending the white supremacist hacker Andrew Alan Escher Auernheimer, known as “weev.” Jeong’s sentiments are similarly distinct from comments made by Kevin D. Williamson, who lost a job at The Atlantic for repeatedly suggesting that women who have abortions be hanged and comparing a black teen to a “primate” and “three-fifths-scale Snoop Dogg.” Abortion providers and patients are targets of real violence in the U.S.; abortion rights are really under threat, from individuals who believe much as Williamson does. White supremacists have murdered people. The Three-Fifths Compromise legally enshrined counting slaves as a fraction of a human. Jeong, meanwhile, cracked some jokes about a racial demographic that dominates her industry, the industry she covers, and the country she inhabits. Distinguishing between those situations isn’t an eccentricity exclusive to a mythical self-serving left: It’s the moral distinction behind an entire genre of literature. The word societies for centuries have used for punching up is satire. The word we generally use for punching down is bigotry.

Without telepathy, it’s impossible to know whether Jeong’s critics understand the gulf that separates her from writers like Norton and Williamson. But whether they understand it or not, the rhetoric they’ve deployed against her aligns all too well with the harassment that has driven her to vent in the first place.

I am far more aggressive on Twitter than I am in my offline life, where I rarely translate internal outrage to external reaction. I have over 36,000 Twitter followers—Jeong has over 69,000—and reading my mentions sometimes feels like holding out an arm for Cerberus to chew. In an average month, Twitter users call me everything from a hack to a whore. If I’m lucky, the comments are random. If I’m unlucky, the comments are part of a wave of similar comments, and that wave can last for days. Surrounded by misogynist abuse intended to silence, I often feel like I have no choice but to shout—much as it seems Jeong did. It’s fair to argue whether venting is the wisest or most effective response, but it’s certainly an understandable one. It may not stop the bigotry, but nothing else does, either.

Human beings write those tweets. They log off and walk in the world beside me. Their opinions do not exist only on the Internet, suspended in amber. Opinions are animating forces. They inform law and policy, and influence interpersonal violence. When a person hates you, when they think you should be punished for what you are or what you believe, manners won’t protect you. You can’t compromise with people who think you shouldn’t be—and who demographically hold the wealth and political clout necessary to codify such beliefs.

The morning after a gunman killed five journalists in Maryland, I walked into a police station to report an emailed threat. It wasn’t graphic, as threats go, just pointed. Whoever wrote it wanted to put me in my place, and that place is silence. For me and for so many other writers who are women or non-binary or people of color, threats exist on the same continuum as harassment and bad-faith interpretations of a person’s statements and work: Whether or not this was their conscious goal, the conservative attacks on Jeong work toward the same end as the troll harassment she lashed out against—to force our departure from the public sphere.

Right-wing writers, even ones who have lost jobs over printed bigotry, do not face anything like the same obstacles. Williamson still places regular bylines, even if they are not at The Atlantic. Damon Linker will probably face no repercussions for comparing Jeong to a neo-Nazi. The American Conservative still employs Dreher, who praised Hungary’s anti-Semitic prime minister with an unequivocal defense of blood-and-soil nationalism hours before calling Jeong a “honky-hater.”

The lines that separate Jeong from a writer like Williamson map onto differences in power, and these are distinctions her critics choose to ignore, comparing a joke at power’s expense to a political philosophy directly responsible for violence, intimidation, and death. The effect of this false equivalence is to shift the so-called Overton window of acceptable political discourse rightward: if you want The New York Times to employ Jeong, these critics insist, the price is to accept open advocacy of white nationalism, hangings for abortion, and more. And by stripping racism of any meaning associated with structural injustice, they absolve themselves of any possible complicity in systemic oppression.

Jeong’s jokes are an affront to many. But they are jokes, launched against a sea of abuse from people who look a lot like those who think she deserves to be fired.

How to Ignore Rudy Giuliani

Earlier this week, Vanity Fair’s Gabriel Sherman reported that Rudy Giuliani, who has served as one of President Donald Trump’s lawyers since April, is falling out of favor in the White House because of a “series of erratic television interviews” this week. “Trump thinks he’s saying too much,” an unnamed source told Sherman. This is a story we’ve heard before: Back in May, the Associated Press reported that Trump was “growing increasingly irritated with lawyer Rudy Giuliani’s frequently off-message media blitz.” And it is a story we’ll probably hear again.

It’s all noise.

The Russia investigation’s myriad threads can be overwhelming to follow, even for the most dedicated observer. The intense secrecy surrounding special counsel Robert Mueller’s work, while giving him a degree of insulation from political attacks, has also made it hard for the public to discern where his investigation stands and where it’s headed. After all, it’s not just Mueller and his team who aren’t talking; few of his targets are, either. Into that epistemic void leaped Giuliani, who gives journalists a steady streams of quotes and comments about the investigation.

This dynamic is increasingly untenable for journalists—or ought to be. Giuliani’s statements cannot be verified, since Mueller would never confirm or deny them, and his modus operandi is clear. He says outlandish things, like that presidents can “probably” pardon themselves or that Trump couldn’t be prosecuted if he murdered James Comey, in order to control the news cycle and muddle the narrative about the Russia investigation, the hush money to former mistresses, and so on.

Finding the signal in this noise is easy enough: Ignore Rudy Giuliani, and pay attention to the narratives that aren’t making daily headlines.

Giuliani’s strategy largely works because his relative fame qualifies him as a newsmaker, and because most other figures in the investigation—including Trump’s other lawyers—are keeping a low profile. It’s also a strategy that Giuliani himself acknowledges.

In June, the Justice Department’s inspector general released a long-awaited report that criticized FBI officials for their conduct during the 2016 election. That evening, Giuliani took to Fox News to demand that Sessions and Rosenstein “suspend” Mueller and shut down the Russia investigation. He also said that Peter Strzok, a former FBI agent who sent texts criticizing Trump during the election, “should be in jail by the end of the week.” These remarks received wide coverage: The New Yorker described the assertion as a “moment of truth for the Republican Party,” while Politico wrote that it represented a “major turning point for the Trump lawyer.” The following week, Giuliani admitted to Politico that his bombastic remarks were a stunt to undermine the Russia investigation’s credibility. “That’s what I’m supposed to do,” he told the reporters. “What am I supposed to say? That they should investigate him forever? Sorry, I’m not a sucker.”

The trend continues. Last month, CNN obtained a recording made by former Trump lawyer Michael Cohen in which he and Trump discussed payments to silence one of his former sexual partners on the eve of the election. The tape’s release was objectively bad news for the president. At a minimum, it conclusively proved that the White House had repeatedly lied about Trump’s foreknowledge of the payments. Giuliani quickly offered a different, credulity-straining version of events: that the tape proved Trump was doing the right thing, by counseling his lawyer to keep the payments above-board. (Whether that’s true is hard to discern due to poor audio quality.)

It’s hardly unusual for someone in Trump’s orbit to mislead reporters and the American public. What sets Giuliani apart is the speed and scale with which he accomplishes these feats. Sherman’s piece came after the former mayor gave a series of madcap, contradictory interviews on Monday. At one point during his whirlwind media tour, Giuliani made the audacious and misleading claim that collusion with foreign powers to win an election is “not a crime,” which dominated headlines for days. At another point, he suggested that Trump may have played a greater role in the infamous Trump Tower meeting in 2016 than was previously known.

What’s more, Giuliani often tells reporters versions of events that can’t be readily corroborated, especially when it comes to Mueller’s activities. Could Trump face criminal charges from the special counsel? Giuliani told The New York Times in May that Mueller’s team has assured him they won’t indict a sitting president. How long will the Russia investigation last? Giuliani said a few days later that the special counsel’s office is aiming to wrap up the obstruction-related part of his inquiry by Labor Day. And because Mueller only speaks publicly through indictments and court filings, there’s no way to tell if Giuliani’s claims are accurate.

To a certain extent, Giuliani is just doing his job: defending his client and discrediting the prosecutor. But there’s also more than just the usual defense work at play here. Shortly after Giuliani joined Trump’s legal team, I noted that he appeared to be managing his presidential client through his media appearances, using his public stature to change the narrative surrounding the Russia investigation. “I’ll give you the conclusion: We all feel pretty good that we’ve got everything kind of straightened out and we’re setting the agenda,” he told The Washington Post shortly after taking the job.

Giuliani isn’t the first lawyer who’s tried to placate Trump with short-term reassurances for long-term legal problems. Ty Cobb and John Dowd, who led the president’s legal team until this spring, kept reassuring Trump and the public that Mueller’s inquiry would wrap up by Thanksgiving, then by Christmas. That timetable was never realistic: The Watergate investigations lasted for more than four years, while the Whitewater probe spanned most of Bill Clinton’s tenure in office. Some observers have speculated that Trump’s periodic eruptions against Mueller—most recently, his demand this week that Sessions shut down the Russia investigation—stem from learning that his expectations don’t match with reality.

Instead of Giuliani’s media sprees and Trump’s remarks, there are three ongoing threads that deserve closer scrutiny. While they only offer a partial window into how Mueller is pursuing his investigation, these glimpses may indicate where the inquiry will go next. Foremost among those threads is Roger Stone. The veteran GOP political operative and longtime Trump adviser played a peripheral role in Trump’s 2016 campaign. Now he appears to be squarely in Mueller’s sights.

In 2016, Stone exchanged messages with Guccifer 2.0, a purported Romanian hacker who played a key role in distributing stolen emails from the Democratic Party and the Clinton campaign during the election. In an indictment unsealed last month, Mueller declared that Guccifer 2.0 was actually a persona adopted by Russian government hackers who had undermined Clinton’s presidential bid. Stone has repeatedly denied any wrongdoing and claimed that he did not know who Guccifer really was.

Mueller has so far sought or obtained testimony and evidence from nearly a dozen people close to the longtime Republican political operative, including former Trump advisers Sam Nunberg and Michael Caputo. In April, the Guardian reported that federal agents stopped Ted Malloch, a professor and political consultant with ties to Stone, at Boston’s Logan Airport and asked him about his interactions with Stone and WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. Malloch told the newspaper that the agents “seemed to know everything about me.” Reuters reported in May that Mueller had issued subpoenas to Jason Sullivan, a social-media consultant who worked with Stone. This week, a federal judge rejected Stone aide Andrew Miller’s effort to quash a subpoena for him to appear before the grand jury.

Mueller’s activities don’t necessarily mean that Stone will be indicted, and it’s unclear what he would be charged with. The sequence of events and the use of a grand jury instead of less formal interviews mirrors the run-up to last year’s indictment of Paul Manafort, Trump’s former campaign chairman, and his former deputy, Rick Gates. In the months before Mueller filed formal charges, multiple aides close to Manafort testified before a grand jury. Manafort is currently on trial in northern Virginia for some of those charges; another trial in D.C. is scheduled for next month.

A second thread of interest worth watching relates to a secret meeting in the Seychelles between Blackwater founder Erik Prince and a Russian banker in 2017. In March, the Post reported that unidentified witnesses have told Mueller that the meeting was set up to establish a back channel between the Trump administration and the Kremlin for unknown purposes. Prince, who is the brother of Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, has denied those allegations. A spokesman told reporters in April that Prince gave the special counsel’s office “total access” to his phones and computer.

Finally, it’s worth following the mercurial story surrounding that Trump Tower meeting in 2016 between Russian lawyer Natalia Veselnitskaya and top Trump campaign officials, including Manafort, Donald Trump Jr., and son-in-law Jared Kushner. A lawyer for Russian pop star Emin Agalarov, who played a role in setting up the meeting, said earlier this week that the special counsel’s office wants to interview his client—a sign of Mueller’s continued interest in one of the key moments so far in the Trump-Russia saga.

Making matters worse for Trump are reports that Michael Cohen is willing to testify that the president knew about the meeting in advance. In this week’s media tour to dispute Cohen’s claims, Giuliani appeared to disclose the existence of a pre-meeting among Trump campaign staffers. The dueling accounts suggest that the story surrounding the Trump Tower meeting could change yet again. If those comments ultimately shed more light on that famous encounter in the summer of 2016, the slip-up may be Giuliani’s most substantive contribution to public discourse all year.

The Media’s Frenzy to Find a Smoking Gun

Since the Russia investigation began, a single question has loomed over it: How will this end? Will special counsel Robert Mueller provide enough evidence to Congress to justify impeachment charges? Or President Donald Trump try to stop Mueller from doing so by triggering a repeat of the Saturday Night Massacre? The most persistent of these questions is also the most pernicious one: Is there a smoking gun that would decisively prove that Trump colluded with Russia to help him win the 2016 election?

Some journalists and observers believe that Trump provided them with one, or at least something close to it, in a tweet on Sunday morning.

Fake News reporting, a complete fabrication, that I am concerned about the meeting my wonderful son, Donald, had in Trump Tower. This was a meeting to get information on an opponent, totally legal and done all the time in politics - and it went nowhere. I did not know about it!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 5, 2018

Trump’s tweet is apparently a response to a Washington Post article about his turbulent state of mind lately. Trump, the paper reported, “has confided to friends and advisers that he is worried the Mueller probe could destroy the lives of what he calls ‘innocent and decent people,’” chief among them his eldest son, Donald Trump Jr. “As one adviser described the president’s thinking, he does not believe his son purposefully broke the law, but is fearful nonetheless that Trump Jr. inadvertently may have wandered into legal jeopardy.”

It’s the latter half of Trump’s tweet, though, that drew the most attention: the acknowledgment that Trump Jr., as well as campaign chairman Paul Manafort and Trump son-in-law Jared Kushner, met with a Russian lawyer at Trump Tower in 2016 “to get information on an opponent,” namely Hillary Clinton. Some journalists saw this as a direct refutation of Trump’s frequent denials of wrongdoing. The Huffington Post reported that the president “finally admits his campaign colluded with Russia at [the] Trump Tower meeting.” The Post’s Jennifer Rubin called the tweet “a gift to prosecutors.” The New Yorker’s Adam Davidson even compared it with the release of President Richard Nixon’s “smoking-gun tape” 44 years earlier to the day, framing it as a signal moment in Trump’s presidency.

It was possible, just days ago, to believe—with an abundance of generosity toward the President and his team—that the meeting was about adoption, went nowhere, and was overblown by the Administration’s enemies. No longer. The open questions are now far more narrow: Was this a case of successful or only attempted collusion? Is attempted collusion a crime? What legal and moral responsibilities did the President and his team have when they realized that the proposed collusion was underway when the D.N.C. e-mails were leaked and published? And, crucially, what did the President know before the election, after it, and when he instructed his son to lie?

While the president’s latest tweet is noteworthy, it’s at risk of being overanalyzed. Trump’s characterization of the Trump Tower meeting is consistent with what the public has known since last summer, when Trump Jr. posted incriminating excerpts from an email conversation with Rob Goldstone, a British music publicist who worked for the son of a Russian oligarch. In that conversation, Goldstone told Trump Jr. that his employer could “provide the Trump campaign with some official documents and information that would incriminate Hillary and her dealings with Russia and would be very useful to your father.” He made clear that this information came directly from Russian government officials and that it was “part of Russia and its government’s support for Mr. Trump.” The president’s eldest son welcomed the offer, writing that “if it’s what you say I love it.” It’s hard to get more conclusive than that.

If anything, Trump’s tweet highlights the extent to which he and his allies can’t get their record straight about that meeting. In a statement in July of last year, after the news broke about the meeting, Trump Jr. insisted that it “was a short introductory meeting. I asked Jared and Paul to stop by. We primarily discussed a program about the adoption of Russian children that was active and popular with American families years ago and was since ended by the Russian government, but it was not a campaign issue at the time and there was no follow up.” His father reportedly played a role in the crafting of the statement. But the following week, Trump Sr. tweeted a different defense—one similar to what he tweeted this past weekend:

Most politicians would have gone to a meeting like the one Don jr attended in order to get info on an opponent. That's politics!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 17, 2017

A week after that, Trump insisted, “I did NOT know of the meeting with my son.” That claim hasn’t been disproven, but Trump Jr.’s phone records show that he called a blocked number at Trump Tower on June 6 while setting up the June 9 meeting. Later that night, the elder Trump told a campaign rally audience in New York that he would give a speech the following week on “all of the things that have taken place with the Clintons.” The curious timing raises questions about whether Trump Jr. told his father about the planned meeting and whether then-candidate Trump approved it.

The Trump Tower meeting itself is already a matter of interest to Robert Mueller. He is still reportedly trying to interview Emin Agalarov, Goldstone’s client and the meeting’s facilitator. The special counsel’s office has questioned multiple witnesses about the circumstances surrounding the meeting, as well as Trump’s role in crafting his son’s statement about it. Michael Cohen, Trump’s former personal attorney, is even reportedly willing to testify that Trump knew about the meeting in advance, which could undermine Trump’s tattered defenses even further.

All of this is already pretty damning. So why was Trump’s tweet treated like a major development in the Russia saga? One answer may lie in the expectations set by past presidential scandals.

Nixon might well have survived the Watergate crisis but for the White House taping system, which provided undeniable proof of his complicity in the cover-up. Most of Watergate’s closing stages—the Saturday Night Massacre, the back-and-forth negotiations with Congress, the Supreme Court’s landmark ruling on executive privilege—revolved around whether those tapes would become public. Once they were, Nixon resigned within days.

Ken Starr’s sprawling investigation into President Bill Clinton’s scandals also failed to turn up a smoking gun until 1998, when Linda Tripp revealed that White House intern Monica Lewinsky had preserved her blue dress after a sexual encounter with the president. A DNA sample from the dress conclusively proved Clinton had lied in denying he had a sexual relationship with Lewinsky. The House of Representatives impeached Clinton for perjury and obstruction of justice later that year, while the Senate acquitted him of the charges in 1999.

Not every investigation turns up evidence that directly implicates a president, however. Inquiries into the Iran-Contra affair in the late 1980s uncovered plenty of wrongdoing by high-level officials in Ronald Reagan’s administration. What it ultimately failed to find was any direct proof that Reagan had sanctioned the illegal diversion of funds to support Nicaraguan rebels. The Tower Commission concluded in 1987 that Reagan “clearly didn’t understand the nature of this operation. Independent counsel Lawrence Walsh’s final report in 1994, six years after Reagan left office, sharply criticized the former president but found insufficient evidence to warrant criminal charges.

Ultimately, the frenzied search for a single piece of evidence that proves Trump illegally colluded with Russia works in his favor. It creates a public expectation that will be difficult for Mueller to meet, thereby setting the stage for disappointment when the inquiry concludes. In doing so, it minimizes the considerable amount of evidence that’s already public: Trump’s supine performance at last month’s Helsinki summit with Vladimir Putin, the constant outreach efforts between the Trump campaign and Russian intermediaries throughout the 2016 election, the sudden dismissal of FBI Director James Comey last May, the persistent efforts to discredit and shut down investigations into what really happened, and so much more.

If this story were a film, it would build to a thrilling climax in which a final bombshell revelation brings down the White House and Mueller walks off into the sunset (or perhaps starts tweeting and writes a book). Real life, however, is rarely so tidy. By holding out for a smoking gun, Trump’s critics may be downplaying the gunpowder residue that’s already coating his hands.

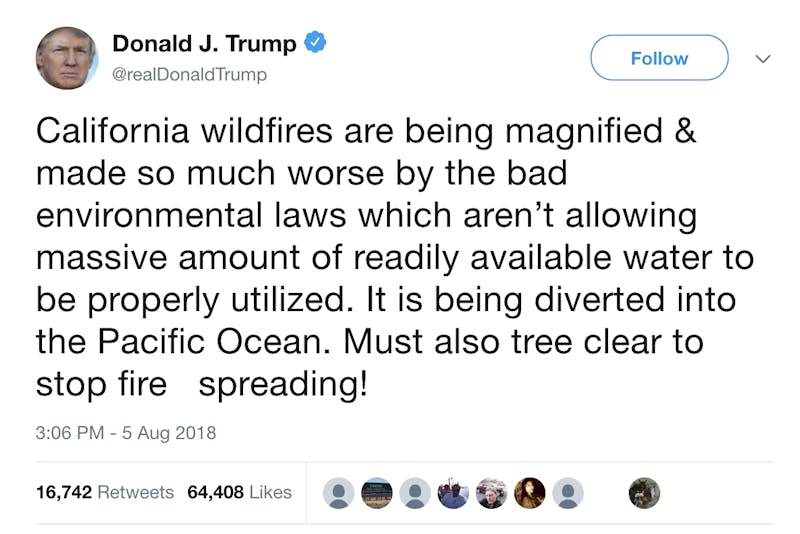

Why Trump Is Blaming California’s Wildfires on Water

Last year was the deadliest and most destructive wildfire season in California’s history. But that soon could change. As the state enters the peak month of fire season, wildfires have already burned more than 290,000 acres and killed eight people. This time last year, only about 220,000 acres had burned, and no one had died. The 2017 season would eventually claim 44 lives.

Why are these wildfires so bad, and why do they seem to be getting worse over time? President Donald Trump offered his opinion in a Sunday night tweet, writing that “bad environmental laws” have been diverting water away from firefighting efforts. He also wrote that the state “must tree clear to stop fire spreading!” (Hours later, he deleted the tweet and tweeted a near-identical version.)

There is an ongoing debate about the merits of “thinning” forests to reduce wildfires, but a lack of available water? That’s not a common complaint of wildfire experts, who instead point to extreme drought and heat, human development in vulnerable areas, and an outdated federal funding system for firefighting.

Presented with Trump’s tweet, the state firefighting agency said it had “no idea” what Trump was talking about. “We have plenty of water to fight these wildfires,” Daniel Berlant, assistant deputy director of Cal Fire, told The New York Times, “but let’s be clear: It’s our changing climate that is leading to more severe and destructive fires.”

What “bad environmental laws” did Trump have in mind, then? On Monday afternoon, he elaborated—sort of.

Governor Jerry Brown must allow the Free Flow of the vast amounts of water coming from the North and foolishly being diverted into the Pacific Ocean. Can be used for fires, farming and everything else. Think of California with plenty of Water - Nice! Fast Federal govt. approvals.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 6, 2018

Some reporters have speculated that Trump is referring to endangered species protections—most importantly, the federal Endangered Species Act. These laws prohibit farmers and other industrial sources from taking lots of water from certain rivers and streams, in order to protect the habitats of endangered fish. Trump is currently seeking to dramatically weaken the Endangered Species Act, so it’s possible he wanted to bolster his administration’s case by linking the federal law to wildfires.

But I think Trump’s tweets reference something more specific: His administration’s escalating attempts to prevent California from regulating its own water systems.

California’s State Water Resources Control Board is expected soon to implement a plan to prevent the imminent collapse of fisheries in the state’s largest estuary. This plan—nine years in the making—would limit water use “in three tributaries to the San Joaquin River, which joins with the Sacramento River to feed into the delta, a key California water source and home to endangered species such as the Chinook salmon,” Pacific Standard reported last month. More water would flow through the system as a whole, so some water would inevitably flow into the ocean, as Trump notes.

Many farmers are opposed to this policy, claiming limits on water use would hurt the agricultural economy. Enter the Trump administration. Last month, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke travelled to two reservoirs in the Northern San Joaquin Valley, where he told reporters that his agency may intervene. “There is a federal interest—the federal interest as the water master,” he said. He was joined by Republican Congressman Jeff Denham, who called the state’s water conservation proposal a “disastrous plan to flush water from valley rivers to the ocean,” foreshadowing the language Trump would eventually use in his Sunday tweet.

Denham has attempted, on several occasions, to enlist the federal government’s help in halting California’s new plan. Most recently, he tucked legislation to stop it in a spending bill for the Department of Interior. Now, he has Zinke and the Trump administration in his corner. Last Friday, the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Reclamation commissioner sent a letter to California’s water board threatening possible legal action if the plan is adopted.

Republicans like Zinke and Denham have long argued that water conservation policies are the real cause of California’s drought—that environmentalists, not climate change or overuse, are to blame for water shortages. But they have never gone so far as to suggest, as Trump did on Monday, that environmentalists are the real reason that wildfires are raging out west. That’s especially concerning because people have died in those fires, as many more likely will. Inventing a bogeyman won’t change that. Only smart policies will.

Mothering and Unmothering

As vocations go, none is so venerated and simultaneously disdained as motherhood. Fraught with essentialized and limiting views of femininity, being a mother often entails demanding recognition for one’s labor while resisting conflation with it. Even as more mothers run for office and take executive positions, countless others are regularly passed over for promotions, based on the assumption that motherhood has whittled down their non-domestic ambitions. It can be nearly as complicated to have a mother as to be one. Every Mother’s Day, those of us who have lost our maternal figures face shrieking pastel reminders of our grief, while those who grew up with abusive or absent mothers are shunted to the side. Our ideals of motherhood both heave with contradictions and lack room for ambiguity.

These are just some of the reasons that Laura June’s joyful, empathic, but uncompromisingly irreverent memoir, Now My Heart Is Full, is such a balm, whether one regards parenthood with clear-eyed enthusiasm or with leery ambivalence. Intertwining her experience of becoming a mother with the memories of her own, late mother, June reckons unflinchingly with the muck of motherhood and daughterhood without disavowing the precious particularities of both. Her book is less preoccupied than other recent works (Sheila Heti’s Motherhood, Rivka Galchen’s Little Labors) with the disquietude inherent to choosing parenthood or with the agitated reconceiving of identity once she has become one; through the tapestry of memory, she tries to forge a new, more capacious narrative for her experiences of motherhood, one that situates pain and pleasure alongside one another, where they neither compete nor cancel each other out.